This

week, I discovered how Wright’s Usonian style endeavored to use his

architecture to both express and mold the shifting American psyche. At the same

time, I tried to determine the educational factors influencing interest in

architectural careers by sending out surveys to the architecture apprentices at

Taliesin West, the high school seniors at BASIS Scottsdale, and sixth- grade

art students at BASIS Scottsdale (Thank you everyone for responding!). More

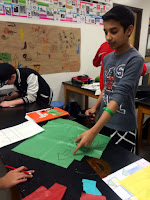

experimentally, Mr. Cleland kindly allowed me to test the effectiveness of my

Robie House geometric leaded glass lesson plan on his sixth grade students. All

this activity will supply data on how Taliesin West can best tailor its

educational outreach to encourage aspiring architects.

_______________________________________________________________________

THINKING

OUTSIDE THE BOX—LITERALLY AND FIGURATIVELY

Not

only was Frank Lloyd Wright continually on a quest to deconstruct the

box—moving supports from the corners to the center, ringing bands of art-glass

windows around the perimeter, innovating glass corner windows—the architect

simultaneously sought to reconstruct American society. In the 1930s, Wright

created two visions for the new American lifestyle: one utopian, the other

practical. His plans for the imaginary Broadacre City proved both fanciful and

foresighted—a more aesthetically pleasing forerunner of Levittown’s later birth

of suburbia. However, his affordable and attractive Usonian homes ushered in a

new era of ranch-style housing for the middle class.

______________________________________________________________________

BROADACRE

CITY

Retreating

from the scandals of his three marriages and two fires in the 1920s—his own

personal Depression years—Wright sought refuge in his work: penning his

autobiography, expanding his Taliesin home to teach students at the Taliesin

Fellowship, and conjuring up an antidote to the rampant urbanization which he

found so unnatural. Wright, together with his apprentices, translated his

social ideals into an architectural model called Broadacre City, which

resembled the yet-to-be created suburbs but with the caveat that every home

would enjoy a small plot of farmland, providing self-sufficiency as a shield to

the Depression-era scarcity. The model of his dream city—actually a

decentralized non-city—toured the country to much acclaim, rebuilding Wright’s

reputation along the way (Thorne-Thomsen, Frank

Lloyd Wright for Kids).

|

| Wright's sketches of Broadacre City; Source: Paleofuture |

|

| Notice futuristic cars and helicopters; Source: Paleofuture |

For

Wright, architectural design could solve social issues such as overcrowding and

alienation of urban life. Technology was to be helpmate to nature. Wright loved

the relatively-new automobile and electricity, giving Americans the freedom to

spread out. Broadacre City seemed a democratic alternative to Soviet communism

of the day: Wright believed that giving every American an acre of land would

restructure society in a more democratic way (Novak, “Broadacre City: Frank

Lloyd Wright’s Unbuilt Suburban Utopia”).

|

| Source: Architecture Daily |

______________________________________________________________________

USONIAN

HOMES

Moving

from fantasy to reality, Wright tackled the need for new, inexpensive housing

as the U.S. climbed out of the Great Depression in the late 1930s and 1940s.

His prior clients had all been wealthy, indulging Wright’s tendency to come in

over budget. Wright perceived that the American lifestyle was changing, and he

wanted a new architecture to serve the needs of the average American.

The

idea for the Usonian house style first came to Wright as he was designing

Broadacre City. While many architects at the time argued that Wright’s

one-family houses were counterproductive to solving the rapid population growth

in cities, Wright viewed “family homes as autonomous estates in a presently

shiftless, rootless mass society and as a humanization of that society” (March,

Forward of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian

Houses: Designs for Moderate Cost One-Family Homes).

|

| Source: Amazon |

No one is quite sure why Wright named this style “Usonian.” Perhaps it is from the

discussion swirling in Europe about whether the acronym for the United States

should be changed to U.S.O.N.A. (The United States of North America) to avoid

confusion with the newly formed Union of South Africa. Whatever the origin, the

name grew to encompass Wright’s vision for the reformed American society he

tried to effect for the last 25 years of his life (Sergeant, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian Houses: Designs

for Moderate Cost One-Family Homes).

Wright

latched on to this idea to describe his desire for a distinctly American

architecture that was both organic and Usonian, stemming from Wright’s belief

that a culture or individual should grow “out of the ground and into the light”

(Sergeant, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian

Houses: Designs for Moderate Cost One-Family Homes).

Usonian

houses were modern, simple, and dynamic, designed to reflect the American

psyche and landscape. Diagonally cutting the box in half, a triangle emerges.

Wright then further deconstructed that triangle, leaving only the L-shaped

edge, an organic shape Wright called a “polliwog” and capable of adjusting to

meet the needs of a growing family (Sergeant, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian Houses: Designs for Moderate Cost

One-Family Homes).

|

| Jacobs House Floor Plan; Source: apartmenttherapy.com |

Often

L-shaped to provide privacy and maximize garden space, these single-family,

one-story buildings were highly standardized and modest to make them affordable

for the average American family. Garages were essential components of the

suburban homes, as Wright recognized the importance of cars to the modern

American (“Key Works of Modern Architecture by Frank Lloyd Wright”).

Wright’s

Usonian houses were not only simple in shape to reduce cost but were

constructed of simple materials: only brick, wooden planks, and glass. Wright

further implemented flat roofs to allow for natural cooling and to remove the

need for rain gutters (rain just ran off). However, possibly the most

innovative aspect of the Usonian houses was their radiant-floor heating

systems. The houses were built on top of a slab of concrete fitted with

hot-water pipes that ran beneath the floor. The heat from these pipes would

radiate through the floor and heat the entire building (“Key Works of Modern

Architecture by Frank Lloyd Wright”).

He

banished squared-off and sealed-off kitchens staffed by hired servants. The

kitchen became a workspace in the center of the house, open to the dining area

which also relinquished its separate room status and morphed into an alcove of

the living room (Lind, The Wright Style).

|

| Source: Usoniandreams.info |

Not

only did Wright eliminate unnecessary walls, he banished the need for skilled

craftsmen by introducing a grid system to make construction what he called

“Usonian Automatic.” These “little do-it-yourself house[s]” epitomized Wright’s

much-praised quality of “tenuity”: steel reinforcing embedded in concrete that

allows push-and-pull and makes it “virtually indestructible,” a technique he

used to build the Imperial Hotel that survived Japan’s catastrophic earthquake

in 1923. Because a worker only needs to follow patterns in the grooved edge of

blocks, skilled craftsmen are not needed (Frank Lloyd Wright, His Living Voice). This inventive horizontal

planning grid—what Wright called a “unit system”—was a rectangle measuring two

by four feet. Masterminding the construction, it was even etched into the

actual concrete floor. Using only two by fours reduced waste further. In this

way, Usonian almost self-build homes further the cooperative communities

espoused in Broadacre City (Sergeant, Frank

Lloyd Wright’s Usonian Houses: Designs for Moderate Cost One-Family Homes).

___________________________________________________________________

JACOBS

HOUSE

Sixth

on the list of Wright’s UNESCO-nominated buildings is the first Usonian house

that Wright built: the Herbert and Katherine Jacobs House, completed in 1937 in

Madison, Wisconsin. Incorporating the above-mentioned Usonian architecture,

Wright delivered a low-cost, simple but elegant, and, above-all, organic home.

|

| Source: usonianvisitorscenter.blogspot.com |

Built

on a small plot of only 144 square-meters, the Jacobs House, like many other

Usonians, has its back to the street, giving residents privacy. The walls on

the side of the house facing the street are composed almost entirely of

horizontal ponderosa pine planks; whereas the walls facing the private garden

are mostly glazed glass, entreating the eye to look outward and for residents

to spend more time outside (“Key Works of Modern Architecture by Frank Lloyd

Wright”).

Not

only was the family connected to nature, but they were connected to each other.

Like Wright’s other homes, the Jacobs house was constructed on an open floor

plan which connected kitchen to dining room to living room, allowing the mother

to watch her children or entertain conversation with guests as she prepared

meals (“Key Works of Modern Architecture by Frank Lloyd Wright”).

Of

course, Wright did not neglect the beauty of the design. Usonian houses boasted their own geometric grill patterns covering windows to inexpensively

reproduce the effects of his leaded-glass windows. The dining alcove was lit by

a “light bridge” made of pine encasing incandescent recessed lighting. Ceilings

were wooden battens composing long geometric patterns (“Key Works of Modern

Architecture by Frank Lloyd Wright”).

|

| The Pope-Leighey House; Source: apartmenttherapy.com |

In

addition to a planning grid which sped up the building process, the Jacobs

House marks the first time that Wright utilized “sandwich-wall” construction of

walls, adding a minimalistic design pattern to the walls, negating the need for

expensive wall décor. Wright’s sandwich walls have three layers: “two pine

boards with a plywood core sandwiched between them.” Form meets function:

redwood battens screw-fashion the surface pine boards on either side of the

insulation-containing plywood core, creating a fireproof and attractive

horizontal pattern (“Key Works of Modern Architecture by Frank Lloyd Wright”).

|

| Source: Mherpy.blogspot.com |

|

| Jacobs House Interior; Source: Pinterest |

Interestingly,

Wright later designed a second Usonian house for the Jacobs in 1948 based on a

solar hemicycle, aligning the sun’s rays to warm the interior, continuing

Wright’s obsession with natural light.

|

| Jacobs House II embedded in an embankment on one side; Source: Ohio.com |

|

| Jacobs House II floor plan; Source: Pinterest |

|

| Jacobs House II Interior; Source: Pinterest |

Other Usonian houses expanded upon the

Jacobs House grid system. The most famous of these is the Hanna House in Palo Alto,

based on the design of a hexagon and the 120-degree angle, instead of the

traditional 90-degree angle, to further deconstruct boxlike rooms (Lind, The Wright Style).

|

| Hanna House; Source: scottlarsen.com |

|

| Hanna House Honeycomb Floor Plan; Source: Pinterest |

|

| Hanna House; Source: Pinterest |

My

lesson plan for the Jacobs House module focuses on creating floor plans for the

new shift of American life in the Information Age—evoking sustainable materials,

green building, and streamlining technology.

WOW! A busy week!

ReplyDeleteWhat was your favorite part of working with the sixth graders? What part was most challenging?

Will you be sharing survey results in coming weeks? Was the response rate highest among a particular demographic?

My favorite part was seeing each sixth grader's different personal interpretation of similar natural forms--their imagination. The most challenging part, however, was getting the students to focus on the detailed work.

ReplyDeleteI might wait for the final presentation to share the survey results, but I probably will make some generalizations soon. The sixth graders had a 100% response rate because they were a captive audience--I handed out the paper surveys before and after the project. So far, I have been pleased with the seniors' response rate--almost 50%. I have yet to find out the results of the M.Arch students' surveys. I will be able to access the survey results later this week.

Your blog is so detailed. I really liked how you linked Wright's architecture with the historical times he lived in.

ReplyDeleteI missed you drawing this week! Although don't be pressured to do them, since I'm sure that they are pretty time-consuming.

ReplyDeleteAnyway, I like that you put a lot of Wright's work into historical context. In this instance, it seems like the Usonian homes were inspired more than by the onset destitution of the Great Depression than the nature that seem to inspire so many of Wright's previous works. Would you say that this is a departure from the previously more environmentally-inspired structures or that there exist precursors of this practicality in them instead?

I think that nature was still the prime motivator for his Usonian houses. Wright, I believe, wanted to design homes so that the average American could appreciate nature in their living spaces. He thought that the new technology could make it easier than ever to do this for everyone, instead of expensive custom work for the wealthy.

Delete